What does your work feel like?

☐ A. It flies by. I a m totally engaged and occasionally even forget to eat or go to the bathroom.

m totally engaged and occasionally even forget to eat or go to the bathroom.

☐ B. I’m bored, watch the clock, and can’t believe this is actually my life.

☐ C. It’s overwhelming, difficult, and sometimes makes me feel like an incompetent idiot.

☐ D. It depends.

If you answered A, then y ou might just want to stop reading and get back to your super fulfilling work. If you answered B, C, or D, and want more flow in your work, stick with me.

ou might just want to stop reading and get back to your super fulfilling work. If you answered B, C, or D, and want more flow in your work, stick with me.

Flow, termed by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced chick-SENT-me-hi), is a state of intense absorption and involvement with the present moment. Flow activity is completely engaging and intrinsically rewarding. In other words, a person engaged in flow doesn’t view the activity as a hoop to jump through. Csikszentmihalyi first identified this “peculiarly positive and complex state of mind through interviews with people whose work or leisure life involved engaging and challenging tasks, such as performing surgery, creating art, climbing mountains, or playing chess” (Fave, 2013, p. 60). These people describe a feeling of absorption and enjoyment as they engage in activities that are high in challenge yet within their control.

On first encounter, it’s easy to think that flow is a bliss only available to the most creative and brilliant among us. However, lately I’ve been thinking how everyone can self-create flow through their current work tasks—no matter the ingredients at hand.

In thinking about this, I’ve mused about the raw materials of my own work as a teacher, researcher, and writer.

I would say that, about 25% of the time, I am pretty engaged in my work. Time literally flies when I’m giving conference presentations, teaching, and leading workshops. Creating lesson plans or designing power points also seems pretty easy and fun. During such periods I feel productive, energized, and in my element.

Fortunately, I rarely am bored or watch the clock. O.k., o.k., except maybe very rarely in one of “those” faculty meetings. And, of course, reference checking is a drag.

More frequently, my work can feel vague, complex, and anxiety producing. Especially when I am trying to write peer-review worthy scholarship, I can feel overwhelmed. This, in turn, sends me scrambling for any reason to take a break (YouTube cat videos, enter stage right). All this flitting back and forth makes me feel guilty, and this toxic mixture of guilt and anxiety does not equate with either a good mood or high productivity. Indeed, a task that “should” have taken 2 hours (and left me with several hours available for favorite leisure activities, like a good movie, yoga class, or coffee with a friend), instead takes all day long.

So, what might we do to proactively create work (or structure work for our team, colleagues, mentees, or students) that produces flow? Nine different characteristics make up flow, but here I focus on three ingredients that seem most important for concocting this magic cocktail of happiness and productivity.

1. Clarify your goals – flow activity is characterized by clear, measurable, and feasible goals.

One of the reasons it’s easy for me to write lesson plans is because the task has feasible, clear, and immediate goals built into it: namely, I have to figure out activities and talking points, by a specific date, that will entertain and educate a specific level of students, about a specific topic, over a specific period of time.

In contrast, goals for academic writing are more amorphous—e.g., “improve this paper; be smarter; figure out why the findings are significant.” And, do this “at some point–probably sooner rather than later, if I ever want to graduate/find a job/get promoted.”

Creating a series of goals, sub-goals, mini-goals, and immediate goals can help create flow for overwhelming and vague tasks. Doing so points to exactly what’s needed to do next. So, in the case of my huge writing tasks, to find flow, a key part is breaking it down to SMART goals (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound); e.g., “edit methods section in the next 20 minutes,” or “reread these four articles today and take notes about what they say on future research needs tomorrow.” With clear goals in hand, focus appears.

When the goal is unclear, it’s impossible to find flow.

2. Seek out and create mechanisms that will provide consistent feedback – flow activity is marked by consistent and quick-turnaround feedback.

Imagine a mountain biker speeding down a dirt trail. The environment provides consistent immediate feedback regarding how well the cyclist is navigating the ride. Bumps, jars, and spills into the cacti help the rider consistently recommit and adjust. This immediate feedback is a key aspect of finding flow.

So, now, consider your own work and the kind of feedback you receive or imagine to receive. Flow is next to impossible without feedback. That’s why it may be easier for students to find flow in regular course assignments than when writing one huge paper that they won’t get feedback on until the end of the term. Writing a five page lesson plan (in which you can imagine students’ reactions and then immediately experience them the next day) is more engaging than writing five pages of a literature review that you don’t imagine a reviewer or advisor will read for another seven months.

So, if you don’t have consistent feedback, you are more likely to find flow if you develop mechanisms that spur feedback. Tactics might include sharing early ideas via social networking sites or a blog, creating a peer review system, or having an “accountability buddy” who will at least see, appreciate, and provide a pat on the back when a task is accomplished (or provide a tap on the shoulder when it’s not).

Imagined and actual feedback are key to finding flow.

3. Structure and create tasks that hit your sweet spot between skill and challenge.

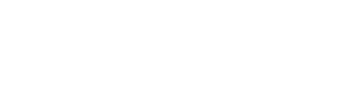

As illustrated in the graphic wheel below, flow occurs at the pinnacle of challenge and skill. Think of skilled jazzed musicians completely engaged in their jamming session, or a pastry chef intently frosting a perfect cupcake. Now, consider your own talents, abilities, and tasks. What are those areas where you are highly skilled, completely engaged, in control of the situation, but not overwhelmed? Those are your flow activities.

Unfortunately, all too often, our work is characterized by less joyous and productive states. First year doctoral students spend too much time in worry and anxiety. Cubicle dwellers may find themselves rotting away from boredom and apathy.

The key to flow is to create and seek out tasks that are a closer balance of skills and challenge. Finding flow on a ski slope requires knowing the runs that are this perfect balance. Too easy? You’re bored and freezing, waiting for friends at the bottom of the bunny hill. Too hard? You get a face full of snow and a chest full of terror.

Of course, to find flow, one needs to cultivate a skill—this skill may be in music, writing, cooking, sports, writing, or quilting—really, anything. Indeed, flow is different than leisure activity in that flow is precipitated by effort and practice. Indeed, to become great at anything, experts suggest 10,000 hours or more of practice.

As we grow older, if we want to continue to create flow, then, we must continue to learn. It’s easy to get comfortable in the “relaxation” area of the above grid—where we have very high skill but low challenge (e.g., cooking up the same tried and true recipe; or continuously relying on the much practiced and perfected lecture rather than creating a new lesson plan). Sure, this doesn’t cause us anxiety. However, playing it safe doesn’t invigorate.

I’ve personally found that in order to eventually create flow in a high challenge activity, I usually must first must push myself into “anxiety” and “arousal.” I’ve done this enough that the memories of past flow (and the energy, joy, and productivity that come with it) are great motivators to get me out of my comfortable routine and try something new. That said, doing new things—like going to a new fitness class or traveling to a foreign country—can still be initially stressful, frustrating, or even embarrassing and scary.

So, in summary, three things to create flow include:

- Clarify the goal – and try to make it SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound).

- Seek out tasks that provide immediate imagined or actual feedback and/or create mechanisms to receive feedback.

- Structure and create activities so that they fall in the sweet spot of complex challenge met with adequate skill.

Do you have other ways of finding flow and engagement in your work? If so, or if you have any other feedback, I would love to hear from you. Also, if you found this post useful, feel free to share it with your own networks. Cheers, Sarah

See here, here, and here for more information on flow. Oh yeah, and here: Fave, A. D. (2013). Past, present, and future of flow. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Happiness (pp. 60-72). Oxford, UI: Oxford University Press