Certainty: The Fool's Drug of Choice

June 23, 2014Possibility Detective

A couple weeks ago, I posted this on Facebook.

Certainty is a small warm cocoon that feels so good, until we realize how it cuts off learning, dialogue, relationship, and creativity. Courage is to break free of this small dark place, shine our soft underbelly to the world, and say, “I don’t know.”

Several friends suggested I write more. Since that time, I’ve written bits and pieces of what follows. None of it seems earth-shattering, but it fleshes out my original post.

* * * * *

Lately, I’ve spent a lot more time with children. I watched my niece and nephew, four and seven, for several days in June, and have been regularly hanging out with my new “Little Sister”, seven-year-old Arianna.

One thing I’ve noticed is their almost constant curiosity. Lydia noticed a tiny squirt bottle of water flavoring in my pantry, and asked, “Aunt Sarah, what’s this?” Zander, in my MiniCooper Clubman, “Aunt Sarah, how fast can you go?” Arianna, “Do you have a house? Does that mean you have a garage?” Their questions, in turn, unfolded into discussions that allowed them to learn something and helped me to appreciate and consider my world anew. Every once in a while, though, I noticed something else in their talk. It unfolded something like this:

Sarah says: “I like to eat a lot of vegetables. They give me vitamins to fuel my body.” The reply: “I know.”

On its face, this response of “I know” is pretty darn innocuous. It’s affirmation. It’s agreement. It’s definitely not counter-argument or trying to make me wrong. So what’s the problem? Why does the response, “I know,” irk?

I suspect there’s lots of reasons—some of them having to do with realizing that children don’t always interpret my unsolicited advice as helpful; others having to do with the fact that most people want to lay claim over some domain of knowledge. However, I think the effect of "I know" is more toxic than that—and that’s what my original Facebook post was about.

Namely, the need to be right, and be certain, and “know” can have a number of problematic consequences. It shuts down dialogue. It shuts down learning. It shuts down creativity and growth.

About right now, you might be saying to yourself, “I don’t reply to others by saying ‘I know,’” or “This is a child thing.” But, as people grow older, it seems we just become increasingly clever in our ways of saying, “I know.” We hide it behind sophisticated screens of logic, facts, research, and sarcasm. We hide it so well that we don't even see it--and this is a bad, bad thing, in several different ways.

First, a posture of “I know” is the enemy of learning. Children are amazing models for not placing significance on or being self-conscious about doing things less than perfectly. If a tiny ballerina cannot twirl yet, he or she makes a delightful mess of spinning until it’s learned. In contrast, when we adopt a posture of “I know,” then it’s a BIG DEAL and SOMETHING IS WRONG when we don’t know or do something perfectly.

Second, “I know” shuts down creativity and growth. “I know” functions as an a priori posture where a person must feel certain and successful before he or she can begin a project or engage in a certain conversation. I’m not knocking planning or education. I've spent more than half of my life in school. Strategies, itineraries, and expertise can serve as great resources for execution and confidence. However, too often we treat our expertise and knowledge not as resources to pull from when useful, but instead as rigid armor that we can never let down. As such, the knowledge and expertise becomes a screen through which the world is known, and becomes a burden that cuts us off from seeing the world and other people freshly, for what they are, TODAY.

When we hold onto our armor of certainty too tightly, we cannot be present for opportunities along the way. We gather all our evidence before we engage in dialogue. We need a perfect outline before we write. We create a strict itinerary before traveling. With these bastions of certainty clutched tightly in our sweaty grip, we see changes in our plan, or questions about our carefully crafted viewpoints, as obstacles to avoid or threats to annihilate. And, in the worst of cases, feeling like we need to know everything first paralyzes us in a stagnant pool of the familiar, mundane, and trivial. We miss out on the myriad adventures of plunging into the unknown.

Third, when we can embrace uncertainty, possibility opens up. The hiccups and outright challenges to our perfect plans / conversations / projects become contributions to the journey rather than reasons to be angry, or to make another wrong, or to chastise ourselves for not knowing better—something that Jon Camp beautifully discusses in relation to travel here.

Indeed, creativity and growth comes through process, flexibility and openness.

When I think about the people I admire, it’s those who consistently have the confidence and courage in themselves to adopt a posture of “I don’t know.” And even, “I don’t know what I don’t know.” Two examples come to mind.

First, for years, Belle Edson led several friends including me on a trip to Rocky Point, Mexico. Belle never knew exactly where we were going to stay when we got there. At first, this made me, a planner, very nervous. However, over time, I realized that her openness to uncertainty about our final destination was what made it possible to stay in the most beautiful locations for an affordable cost. We certainly could have reserved a place in advance, but it would have been much smaller and more expensive. Certainty comes with a price.

Second, a great example of living in a space of “I don’t know” is my mom, Malinda. She’s an educated 73 year-old that I’m confidant could have handily gotten through life based solely on the knowledge she’d accumulated by age 40. However, even as she has retired and moved to Arizona, she has continued to learn and grow. She reads “how to” and personal growth books (in addition to many others), takes swimming lessons, and is open to unfamiliar and alternative medical approaches. Because of this, she’s learned new ways of coping and flourishing as she serves as a primary caretaker for her husband, has become one of the fastest senior swimmers in the country, and has received and practiced physical therapy so she can remain physically fit. She is vibrant, alive, and always asking questions.

It’s a lot of fun to be around people who take a posture of “I don’t know.” In contrast, it’s not so delightful to be around people who are always in a space of truth and certainty. People who must always be right in conversation, by default, make other people wrong. From such a vantage, conversation is not a dance of ideas in which we might emerge on the other side as better informed or gaining new insight. Rather, it is a battle of “I’ll show her,” and “I’ll get him.” Even when we agree with such people, being around “I know” is exhausting, stale, and anxiety-producing.

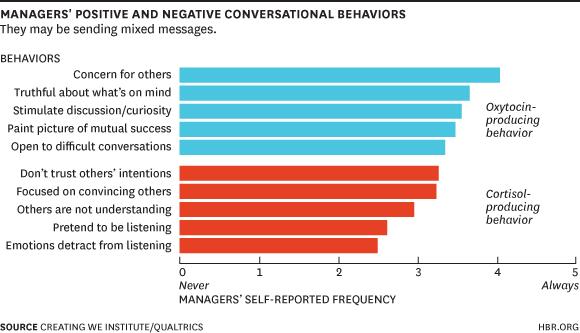

This is backed up with the latest neurochemistry research available via the Harvard Business Review. According to this research, people create oxytocin (a feel-good hormone) in response to conversations that stimulate discussion and curiosity. In contrast, when people face those who are focused on convincing others, their bodies create cortisol (a hormone that shuts down the thinking center of our brains, activates conflict aversion and protection behaviors, and is linked to anxiety and weight gain).

Of course, there’s good reason why we hold onto a stance of, “I know.” Like a drug, certainty is intoxicating. It feels good. But its high is hollow and short-lived. Certainty clings to past plans, expertise, opinions, beliefs, values and can cut us off from living life as lived—in all its glorious messiness and ambiguity—TODAY.

Adopting an “I don’t know” approach to life also takes courage and vulnerability. There are people in life (especially those heavily shielded with the armor of certainty) who pounce upon others’ vulnerability like drug addicts craving their next hit. I was target in such a situation recently when one of my Facebook friends asked, “Why would anyone support Obama in this latest terrorist situation?”

I answered something like, “I haven’t been following the story in the last several days as I’ve been watching my niece and nephew. I’ve heard bits and pieces from The Daily Show and NPR. Maybe I’ll read up and get back to you after I get back to my regular news routine.” In response, I was immediately met, with, "I have noticed most Obama voters get their information from places like Facebook and the Daily Show." Bam!

In this situation, my saying, “I don’t know” (and sharing my current knowledge sources) was invitation to get my belly squashed. It stung a bit, but I wasn’t terribly surprised given the history of what has showed up on this person’s Facebook feed. Despite the sting, having my belly squashed really isn’t that bad compared to living in a dark, small, and suffocating space called certainty. It seems better to live life with adventure, creativity, vulnerability, and growth—in a posture of “I don’t know”—even when it means some scars and bruises along the way.

Of course, I may be wrong.

A Bricoleur Bakes

March 10, 2014Possibility Detective

This is a story about baking a first cheesecake. But, before that, another little tale:

Brad and I enjoyed a lovely breakfast this morning at BLD. Brad ate most of his “Hatch Hash,” but left virtually untouched a small pot of chorizo queso. Before the waiter could whisk it away, I got it safely packaged into a to-go cup. I have no idea of the chorizo’s ultimate destination, but in the next few days, it will add some spicy richness to some lucky dish--likely a soup or stew.

This is my normal way of cooking. I tinker. I use leftovers. I don't use recipes as designed—but instead refer to several in combination as brainstorming tools. I’m a big fan of peering into the fridge and pantry, then Googling the names of several ingredients (e.g., quinoa, spinach, pumpkin), seeing what comes up, and creating a unique concoction from there.

In other words, I’m a kitchen bricoleur.

Bricolage, French for “tinkering”, refers to the practice of creating work by pulling from a diverse range of materials that just happen to be available. My cooking is like my research. I rarely begin my projects with crystal clear purposes or instructions. Instead, I look around and see what’s available—adding a little of this, a little of that, tasting, and then modifying as I go. This works great for ~75% of what I cook and so-so for the other 20%. Every once in a while, it completely flops.

My method stands in stark contrast to that of my love, Brad, who starts with a recipe, purchases the proper ingredients, and follows the instructions. Brad, by the way, has a much higher yumminess success rate. But, it also costs more money and requires more up-front planning.

Anyway, this week, I wanted to make cheesecake.

And cheesecake is a chemistry project.

Bricolaging it in my traditional manner was not going to do for a cheesecake.

Therefore, and completely against my nature, I studied a recipe. Then I went shopping. Then I actually FOLLOWED the recipe. Okay, maybe not exactly, but mostly. And the result was, by all accounts, pretty dang successful.

Here, I provide a step-by-step of the process—as unlike most my cooking, this process can actually be replicated.

And, the process has also inspired some philosophical reflections (feel free to skip the next three paragraphs if you want to get right to the baking).

First, I think we could learn a lot about people’s research inclinations (deductive/scientific/positivist vs. inductive/humanistic/interpretive) by asking them how they usually go about cooking. And, we might be able to learn something about trying to cook in the opposite way than our nature. I’ll never give up my bricolage ways. However, this week, I definitely felt the advantages of baking with a recipe and set of instructions in hand. Doing it this way gives me a little insight into the advantages of a clear purpose, a priori research design, and being able to repeat the process!

Second, there are clear benefits of living with someone like Brad who has the opposite cooking style. Between the two of us, we have a great mix of good old reliably yummy dishes (from Brad), and decent dishes that creatively use up the leftovers (from me). Maybe we could usefully view the research field the same way, and rather than engaging in the same old tired paradigm wars, see how different styles complement (and need) each other.

Finally, it's no coincidence that it’s only on sabbatical that I baked a cake – where I have time and space to experiment, check and double check my work, and risk error without awful repercussions. It reminds me that giving myself space and grace for potential failure is a catalyst for feeling courageous enough to try new things.

Anyway, enough philosophizing, here’s the run-down on the cheesecake. I began with a low-sugar recipe available here. I made a couple modifications. First, I added a ginger snap crust available here. Further, I only added 2/3 of the Spenda called for. Also, I didn’t have a spring form pan, so used a “deep dish baker” from Pampered Chef that my step-mom Judi got my years ago. I also added a pan of water at the bottom of the oven (adds humidity so the cake doesn't crack). Finally I swapped cream cheese for lower fat Neufchâtel. Otherwise, I followed the instructions.

The next day, I topped the cake with raspberry jelly, first heated in a pan and then poured on top. I placed the cake into the freezer for a few minutes to firm it up.

Then, I whipped my own heavy cream, adding a couple tablespoons of Splenda and a teaspoon of Vanilla. I placed the whipped cream in a Ziploc baggy, took the cake out of the freezer and piped it onto the top. Then I topped half the cake with Truvia sweetened dark chocolate chips and the other half with raspberries.

Since I couldn’t decorate the sides of the cake, I decorated the platter with flower cuttings.

I hope this inspires you to try out the cake or another cooking style. Let me know how it goes, and feel free to post any questions.

Arizona Republic

A story highlighting my scholarly work on creating healthy habits. Valley Residents Resolve to Improve Lives in Ways Big and Small. Contributor to a story on creating healthy habits.

Click here to read!

Creating Flow at Work

September 3, 2013Possibility Detective

What does your work feel like?

☐ A. It flies by. I a m totally engaged and occasionally even forget to eat or go to the bathroom.

m totally engaged and occasionally even forget to eat or go to the bathroom.

☐ B. I’m bored, watch the clock, and can’t believe this is actually my life.

☐ C. It’s overwhelming, difficult, and sometimes makes me feel like an incompetent idiot.

☐ D. It depends.

If you answered A, then y ou might just want to stop reading and get back to your super fulfilling work. If you answered B, C, or D, and want more flow in your work, stick with me.

ou might just want to stop reading and get back to your super fulfilling work. If you answered B, C, or D, and want more flow in your work, stick with me.

Flow, termed by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced chick-SENT-me-hi), is a state of intense absorption and involvement with the present moment. Flow activity is completely engaging and intrinsically rewarding. In other words, a person engaged in flow doesn’t view the activity as a hoop to jump through. Csikszentmihalyi first identified this “peculiarly positive and complex state of mind through interviews with people whose work or leisure life involved engaging and challenging tasks, such as performing surgery, creating art, climbing mountains, or playing chess” (Fave, 2013, p. 60). These people describe a feeling of absorption and enjoyment as they engage in activities that are high in challenge yet within their control.

On first encounter, it’s easy to think that flow is a bliss only available to the most creative and brilliant among us. However, lately I’ve been thinking how everyone can self-create flow through their current work tasks—no matter the ingredients at hand.

In thinking about this, I’ve mused about the raw materials of my own work as a teacher, researcher, and writer.

I would say that, about 25% of the time, I am pretty engaged in my work. Time literally flies when I’m giving conference presentations, teaching, and leading workshops. Creating lesson plans or designing power points also seems pretty easy and fun. During such periods I feel productive, energized, and in my element.

Fortunately, I rarely am bored or watch the clock. O.k., o.k., except maybe very rarely in one of "those" faculty meetings. And, of course, reference checking is a drag.

More frequently, my work can feel vague, complex, and anxiety producing. Especially when I am trying to write peer-review worthy scholarship, I can feel overwhelmed. This, in turn, sends me scrambling for any reason to take a break (YouTube cat videos, enter stage right). All this flitting back and forth makes me feel guilty, and this toxic mixture of guilt and anxiety does not equate with either a good mood or high productivity. Indeed, a task that “should” have taken 2 hours (and left me with several hours available for favorite leisure activities, like a good movie, yoga class, or coffee with a friend), instead takes all day long.

So, what might we do to proactively create work (or structure work for our team, colleagues, mentees, or students) that produces flow? Nine different characteristics make up flow, but here I focus on three ingredients that seem most important for concocting this magic cocktail of happiness and productivity.

1. Clarify your goals – flow activity is characterized by clear, measurable, and feasible goals.

One of the reasons it’s easy for me to write lesson plans is because the task has feasible, clear, and immediate goals built into it: namely, I have to figure out activities and talking points, by a specific date, that will entertain and educate a specific level of students, about a specific topic, over a specific period of time.

In contrast, goals for academic writing are more amorphous—e.g., “improve this paper; be smarter; figure out why the findings are significant.” And, do this “at some point--probably sooner rather than later, if I ever want to graduate/find a job/get promoted."

Creating a series of goals, sub-goals, mini-goals, and immediate goals can help create flow for overwhelming and vague tasks. Doing so points to exactly what’s needed to do next. So, in the case of my huge writing tasks, to find flow, a key part is breaking it down to SMART goals (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound); e.g., “edit methods section in the next 20 minutes,” or “reread these four articles today and take notes about what they say on future research needs tomorrow.” With clear goals in hand, focus appears.

When the goal is unclear, it’s impossible to find flow.

2. Seek out and create mechanisms that will provide consistent feedback – flow activity is marked by consistent and quick-turnaround feedback.

Imagine a mountain biker speeding down a dirt trail. The environment provides consistent immediate feedback regarding how well the cyclist is navigating the ride. Bumps, jars, and spills into the cacti help the rider consistently recommit and adjust. This immediate feedback is a key aspect of finding flow.

So, now, consider your own work and the kind of feedback you receive or imagine to receive. Flow is next to impossible without feedback. That’s why it may be easier for students to find flow in regular course assignments than when writing one huge paper that they won’t get feedback on until the end of the term. Writing a five page lesson plan (in which you can imagine students’ reactions and then immediately experience them the next day) is more engaging than writing five pages of a literature review that you don’t imagine a reviewer or advisor will read for another seven months.

So, if you don’t have consistent feedback, you are more likely to find flow if you develop mechanisms that spur feedback. Tactics might include sharing early ideas via social networking sites or a blog, creating a peer review system, or having an “accountability buddy” who will at least see, appreciate, and provide a pat on the back when a task is accomplished (or provide a tap on the shoulder when it’s not).

Imagined and actual feedback are key to finding flow.

3. Structure and create tasks that hit your sweet spot between skill and challenge.

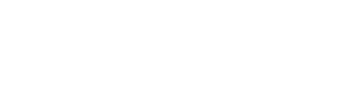

As illustrated in the graphic wheel below, flow occurs at the pinnacle of challenge and skill. Think of skilled jazzed musicians completely engaged in their jamming session, or a pastry chef intently frosting a perfect cupcake. Now, consider your own talents, abilities, and tasks. What are those areas where you are highly skilled, completely engaged, in control of the situation, but not overwhelmed? Those are your flow activities.

Unfortunately, all too often, our work is characterized by less joyous and productive states. First year doctoral students spend too much time in worry and anxiety. Cubicle dwellers may find themselves rotting away from boredom and apathy.

The key to flow is to create and seek out tasks that are a closer balance of skills and challenge. Finding flow on a ski slope requires knowing the runs that are this perfect balance. Too easy? You’re bored and freezing, waiting for friends at the bottom of the bunny hill. Too hard? You get a face full of snow and a chest full of terror.

Of course, to find flow, one needs to cultivate a skill—this skill may be in music, writing, cooking, sports, writing, or quilting—really, anything. Indeed, flow is different than leisure activity in that flow is precipitated by effort and practice. Indeed, to become great at anything, experts suggest 10,000 hours or more of practice.

As we grow older, if we want to continue to create flow, then, we must continue to learn. It’s easy to get comfortable in the “relaxation” area of the above grid—where we have very high skill but low challenge (e.g., cooking up the same tried and true recipe; or continuously relying on the much practiced and perfected lecture rather than creating a new lesson plan). Sure, this doesn’t cause us anxiety. However, playing it safe doesn’t invigorate.

I’ve personally found that in order to eventually create flow in a high challenge activity, I usually must first must push myself into “anxiety” and “arousal.” I’ve done this enough that the memories of past flow (and the energy, joy, and productivity that come with it) are great motivators to get me out of my comfortable routine and try something new. That said, doing new things—like going to a new fitness class or traveling to a foreign country—can still be initially stressful, frustrating, or even embarrassing and scary.

So, in summary, three things to create flow include:

- Clarify the goal – and try to make it SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound).

- Seek out tasks that provide immediate imagined or actual feedback and/or create mechanisms to receive feedback.

- Structure and create activities so that they fall in the sweet spot of complex challenge met with adequate skill.

Do you have other ways of finding flow and engagement in your work? If so, or if you have any other feedback, I would love to hear from you. Also, if you found this post useful, feel free to share it with your own networks. Cheers, Sarah

See here, here, and here for more information on flow. Oh yeah, and here: Fave, A. D. (2013). Past, present, and future of flow. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Happiness (pp. 60-72). Oxford, UI: Oxford University Press

The Single Most Important Lesson of the Latest School Shooting

August 26, 2013Research,Possibility Detective

For the last week, America has marveled at the behavior of Antoinette Tuff, credited as the unlikely hero who prevented the would-be school shooting in DeKalb County, Georgia.

As a quick summary, 20 year old Michael Brandon Hill entered McNair Learning Academy August 20th, packing nearly 500 bullets, weighed down by extra magazines, an AK47-type rifle, and a committed resignation that he would die that day. It was a Sandy Hook massacre in the making—a toxic mixture of a troubled young man, a long history of mental unbalance, and enough ammo to shoot more than half the student body.

But, someone turned that around. After Mike snuck through the security door behind a parent, he was met by front office employee Antoinette Tuff who, over the next couple hours, talked him down—or more precisely, talked him “up” and “through”—his shoot-out plans. Miraculously, no one—not the police, the children, the staff, nor the shooter himself—was physically harmed.

Much of Antoinette’s discussion with the shooter is recorded via a 911 call, a call that should be required listening for police officers, hostage negotiators, or anyone desiring an education in effective negotiation strategies (abbreviated and full version are available). Antoinette offers additional insight in her first interview after the ordeal.

“She did all the things we try to teach negotiators,” said Clint van Zandt, former FBI profiler and hostage negotiator, on NewsNation Thursday. “She was a great ‘go-between,’ she identified with the aggressor, she offered help, she minimized what he had done, she helped develop a surrender ritual, she told him what to expect, and told the police what to expect, she offered love, said she was proud of him, she offered him a positive future–every one of those things is something we spend weeks teaching negotiators, and this lady did it intuitively.”

Even more, right before his surrender, Antoinette took care to ensure the police would not harm the boy (even offering to shield him as he gave himself up), and helped him navigate a last drink from his water bottle.

Since the ordeal, analyses have examined religious lessons learned, how we can train a hero, and whether courage can be taught. These are all good issues, and in the future I may pursue a close discourse analysis of the call.

However, here, I want to focus on what I believe to be the single most important lesson we can learn from Antoinette.

It is this: the mere choice to communicate may be the most important component for practicing compassion.

When faced with an angry, irritated, un-medicated, and violent young man, Antoinette could have easily chosen anger, fear, violence, or distress. Rather than lashing out, isolating him, or fleeing herself, she instead invited Mike back into her office and began to talk and be with him. Through her verbal and nonverbal immediacy, she then recognized his pain, related to him empathetically, and reacted with respect and care.

On its face, this idea—the mere choice to be with another and communicate—is obvious. That is why perhaps it’s so easy to overlook it as a key part of compassion. Indeed, this component is missing in the latest theoretical models of compassion (e.g., Way & Tracy, 2012; Miller, 2007). However, as Antoinette’s case clearly illustrates, the mere choice to communicate is something we should pay more attention to as the crucial catalyst for empathy, civility, and care.

Timothy Huffman, ASU doctoral alum and new assistant professor at Loyola Marymount University, makes a powerful case for the importance of “compassionate presence” as a necessary and overlooked component of compassion in his 2013 dissertation. He asks (p. 82):

- How can someone notice the suffering of someone they cannot see?

- How can a person relate to someone they are not with?

- And finally, how does one act to address a need held by a person who is nowhere to be found?

Huffman argues based upon his research with homeless young adults that, “One cannot recognize, respond, or react without some form of presence. Presence, it seems, is a necessary condition for other functions of compassion to move forward” (p. 82).

And compassionate presence is what we see in the case of Antoinette.

Let’s consider a related topic of negotiation and how, for a long time, an obvious but key part was missing in terms of explaining how or why negotiation was successful. The topic of salary and purchase negotiation has a rich history, with much research explaining various factors—e.g., who makes the first offer, the ordering of concessions, the severity of stance, and so on—and their impact on negotiation success. However, in many situations, these factors don’t matter one wit.

So, what’s the difference that makes a difference? In many cases, it’s choosing to negotiate in the first place.

This simple but crucial factor is powerfully illustrated in Babock and Laschever’s Women Don’t Ask where they demonstrate, among other things, that men initiate negotiations about four times as often as women—and these initiations are crucial in terms of men’s increased lifetime earnings and professional success. The takeaway? Successful negotiation requires that the person recognize the situation as one to negotiate to begin with. If you don’t bother to ask for a raise or a better price, a truckload of negotiation skills aren’t going to matter.

It’s the same with compassion. Just initiating nonverbal immediacy and communication is a crucial compassion skill.

Of course, initiating compassionate presence (just like initiating negotiation) is easier said than done. Contextual, environmental, and biological cues can serve as stumbling blocks.

Recent neuroscience research shows that when people see images of people unlike them, their first instinct is not compassion. As reported by The Greater Good, “Within a moment of seeing the photograph of an apparently homeless man, for instance, people’s brains set off a sequence of reactions characteristic of disgust and avoidance…as if people had stumbled on a pile of trash.”

Despite these instant responses, human beings do have some control in the matter. Namely, if we take just enough time and care to be with the “other” person, our instant biases are moderated. For example, noted in the same Greater Good article, Ohio State researcher William Cunningham found that despite the fight or flight response in white people who see black faces for just 30 milliseconds (so short that it amounts to subconscious exposure), when they “had the chance to see black faces for a bit longer (525 milliseconds) and process them consciously…they showed increased activity in brain areas associated with inhibition and self-control. It was as if, in less than a second, their brains were reining in unwanted prejudices.”

Likewise, some of the latest brain scan research indicates that, “people stop dehumanizing homeless people and drug addicts when they’re made to guess what these people would like to eat, as if the study participants were running a soup kitchen.”

In other words, taking a moment to connect and focus on the other as a person can trigger compassion and empathy. Antoinette’s actions, along with this brain scan research, support the Contact Hypothesis, which states that under the right conditions, contact between members of different groups can reduce conflicts and prejudices.

So, we can take a lot away from Antoinette’s courage and empathy in that Georgia Elementary School front office. However, perhaps the most basic lesson is that great things can emerge when we take a moment to be verbally and nonverbally close to another.

Many people have called for ways the government should honor Antoinette as a national hero. But we can also honor her individually, another way.

Specifically, we can choose to spend a bit more time and communicative space with people who, on their face, may look and act quite differently than ourselves—people who we may otherwise be inclined to treat as dangerous, unfriendly, unworthy, or just odd.

In doing so, we might practice “compassionate presence,” a key component to compassion, empathy, courage, and, perhaps, even heroism.

Tips from a Reformed Flossing Slacker

August 12, 2013Possibility Detective

Over the last year, I have listened and re-listened to the audio--book "The Power of Habit" by Charles Duhigg. This book has profoundly affected how I evaluate my daily activities, and specifically, how I might create habits that best serve me.

According to research, ~90% of our behavior is habitual. Why? Habits are easy. They don't require thinking. Habits are automatic

Given the huge percent of our life that's habitual, if we want to change or transform our life, we must, literally, transform our habits.

Sabbatical, and the change in routine that comes with it, is a perfect time to actively re create a few habits. There have been several habit changes I've been up to, but perhaps the one I'm most pleased with is...

create a few habits. There have been several habit changes I've been up to, but perhaps the one I'm most pleased with is...

FLOSSING.

During our "goals" unit in happiness class this summer, I reported with pride to my students that I had been flossing every day for the last three weeks. Rather than, "Wow, Dr. Tracy, that's really swell," I instead was met with simultaneous uptakes in breath, and cries of, "ewww...". One student exclaimed, "Only for the last three weeks? That's DISGUSTING!" I recouped. "It's not like I never floss, it's just, well, maybe, that I, well, 'ya know, I floss, like, if I know there's something caught in my teeth or something." They were decidedly unimpressed.

Despite my students' shock, the statistics suggest that I'm not alone as a floss slacker. According to one article, only 12% of American floss daily. If you're one of the grimy 88% rest of us, and you're interested in changing this habit, here's some tips about how I've made the switch.

1. I purposefully scared myself. During my last dental cleaning in April, I literally turned to my lovely hygienist and said, "I need you to put the fear of god into me about flossing." She looked a bit surprised, and then asked, "Seriously?" With my gums still smarting, she delightfully described what happens to non-flossers.

In addition to gum disease, effects of not flossing include gingivitis and CANCER. Yes, cancer, and specifically pancreatic cancer, is linked to the bacteria and inflammation that enters the body every day when you don't floss.

Not flossing also makes your gums recede. If want a flossing kick-start, do an image search on "gum disease." Just don't do it while you're eating.

And, finally, letting the food rot in between your teeth (40% of the teeth total surface), is just gross. My hygienist said, "Some people say they don't floss because when they do, it smells like rotting meat." Arg! So, not flossing is kind of like perpetually french-kissing a variety of mini carcasses.

2. I planned and strategized how to make it "easy." For me, this meant buying "satin" dental floss that would slide easily between my teeth, and setting out this floss in a prominent easy to see location. In sight - in mind.

3. I began the goal during a time when my routine was already disrupted. Habits are location and time based. So, a perfect time to stop a bad habit or begin a new one is when your routine is already out of whack. I began the flossing habit over my seven weeks out of the country this summer. My evenings there were inherently somewhat different, and my bathroom stuff in a little visible hanging bag, so switching just one more thing to my nighttime line-up wasn't exponentially more difficult.

4. I talked about my new habit. Specifically, I told Brad, my mom, my hygeinist, and my students. What's more, I encouraged them to ask me about how I was doing. Talking to others makes it real, and provides an automatic accountability loop.

5. I practiced the habit at the same time every day. I flossed right before bed. Habits are most easily formed when they are performed the same way in the same time every day. That way, they become automatic. No more decisions.

6. Skipping a day wasn't an option. I told myself that flossing had to happen every night, no matter how late, busy, or sleepy I was.

7. The habit was linked to a small reward. For me, that was rinsing with mouthwash. Mouthwash provides a tingly zing that I've come to love, and one that I now associate with flossing. Research shows that good habits are much better formed when coupled with a reward. And, bad habits are shaken when we can find a new reward to replace the reward of the old behavior. E.g., if 2 p.m. used to equate with a sweet treat, maybe now 2 p.m. is rewarded with a short stroll around the office or Facebook.

The impact of all this is that I've now been flossing every day since Thursday, May 2nd--well above the 66 days research shows it takes for a new habit to "stick." That said, flossing has not yet become completely automatic. I think, though, soon, it will be (and this blog post may indeed cement it...see tip # 4).

So, for all you fellow FLOSSING SLACKERS out there, I invite you to join me in the journey to never again go to sleep with mini carcasses in your mouth. And, if you have any related tips, stories, or challenges about flossing or any other habits, I'd love to hear from you.

Cheers, Sarah

A Crystallized Blog

Welcome to my brand new blog and website!

They are both part of my 2013-2014 sabbatical adventure in which I'm committed to (re)creating a multi-faceted crystallized self. For me, this means I am not only fulfilling my already-pledged sabbatical research projects, but engaging in a whole range of other activities--travel, fitness, family, fun, and food, among others.

Some of you may be wondering what I mean by a crystallized self.

Angela Trethewey and I came up with this concept about ten years ago, and wrote about it in a Communication Theory article (Com Theory - Tracy & Trethewey). The article is mostly a theoretical analysis of identity, but the point I want to make here is that it's easy for people today to have "flattened" identities that are shaped by messages that come from just a few different sources. This can happen, for instance, when we immerse ourselves only into our work or if we surround ourselves with people who have the same beliefs, backgrounds, or ways of being than we do.

Flattened identities have unfortunately become all too common in the United States. As discussed in the books, Bowling Alone, and Alone Together, Americans suffer from having fewer meaningful relationships with friends, neighbors, and fellow community members. Meanwhile, niche television, journalism, and social networking makes it all too easy to only converse with people who are similar to ourselves. I'm not immune to this. I tend to regularly get lost in my work, and I admit to being guilty of quickly shutting the garage door to avoid chatting with the neighbors (although Brad and I recently realized how great our neighbors are--even the one we labeled as a troublemaker)!!

I believe that one ameliorative to these disappointing trends that flatten our identity is to actively seek out a variety of experiences, in different contexts, and with different people. This is a key part of creating a crystallized self. As one of my favorite researchers, Laurel Richardson, explains, "Crystals grow, change, alter, but are not amorphous. Crystals are prisms that reflect externalities and refract within themselves, creating different colors, patterns, and arrays, casting off in different directions. What we see depends upon our angle of repose (Richardson, 2000, p. 934)."

In other words, crystals are beautiful precisely because they have so many sides to them. This year, I am committed to living a crystallized multidimensional self--the more facets, the better. This will (and already has) put me out of my comfort zone--as I've traveled to foreign lands where I definitely don't speak the language (including France and the cross-fit gym just a mile away). But I guess that discomfort is kind of like the blistering hot conditions that shape real crystals. So, I say, bring it on!

This blog will be part of my journey. I envision it as an oasis of inspiration, where I can discuss a whole variety of topics--including different aspects of my research and teaching, but also life philosophies and approaches, fitness, food, fun, family...who knows?

I invite you to join me on the journey and forward posts to anyone who might be interested--and feel free to offer any feedback or thoughts along the way on the blog or the website under construction. Indeed, part of creating a crystallized self is creating opportunities for dialogue with all kinds of people--including YOU.

Richardson, L. (2000). Writing: A method of inquiry. In. N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 923–948). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tracy, S. J., & Trethewey, A. (2005). Fracturing the real-self↔fake-self dichotomy: Moving toward crystallized organizational identities. Communication Theory, 15, 168-195. Com Theory - Tracy & Trethewey [Article protected by copyright laws and provided for educational use]

Sunshine For SunDevils Project

Sunshine for Sun Devils encourages kindness through action. A story about PWWL’s Sunshine for SunDevil’s project.

Compassion: Cure for an Ailing Workplace

EHS Today, The Magazine for Environment, Health and Safety Leaders. Compassion: Cure for an Ailing Workplace (picked up my column written for NCA’s Communication Currents.

Click here to read!

Forbes Magazine

I contributed to articles on work-life balance and workplace bullying.

Van Dusen, Allison (March, 24, 2008). Ten Signs You’re Being Bullied at Work. Forbes. Referencing our workplace bullying research and Project for Wellness and Work-Life.

Farrel, M. (10/2007). So, you married a workaholic: When your partner’s real partner is work, here’s what to do. Forbes. Interviewed and quoted in the article.